Below is a description of each section of the journal, along with suggestions about how to use it.

ARTICLES provide practical, innovative ideas for teaching English, based on current theory.

READER'S GUIDE corresponds to the articles in each issue and can guide your own understanding as well as discussions with colleagues.

TEACHING TECHNIQUES give English teachers the opportunity to share successful classroom practices.

MY CLASSROOM focuses on one teacher’s classroom and describes ways that the teaching environment shapes learning.

TRY THIS gives step-by-step instructions for carrying out activities in your classroom.

THE LIGHTER SIDE features an English language–based puzzle that can be photocopied and given to students to solve individually or collaboratively.

You can use the same pre-, during-, and post-reading approach to reading Forum articles that you might recommend to students. Before reading, consider the title and scan the text; then answer these questions:

- What do I expect this article to be about?

- What do I already know about this topic?

- How might reading this article benefit me?

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- What assumptions does the author make—about teaching, teachers, students, and learning?

- Are there key vocabulary words that I’m not familiar with or that the author is using in a way that is new to me? What do they seem to mean?

- What examples does the author use to illustrate practical content? Are the examples relevant to my teaching?

After reading, consider answering these questions on your own and discussing them with colleagues:

- How is the author’s context similar to and different from my own?

- What concept—technique, approach, or activity—does the author describe? What is its purpose?

- Would I be able to use the same concept in my teaching? If not, how could I adapt it?

Search for related articles at americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum; the archive goes back to 2001. Submission guidelines are also posted on the website. Email manuscripts to etforum@state.gov.

|

Youth in middle and secondary grades, between childhood and the adult world, sometimes struggle with their identities as readers and learners. Too many describe themselves or are described by their teachers and parents as “reluctant, disengaged, and/or unmotivated” by classroom texts or by the rows of books in school libraries.

Even though blockbuster series have powered young adult fiction and cinematic markets over the last two decades (e.g., Harry Potter The Hunger Games Diary of a Wimpy Kid), “I don’t like to read” is nevertheless a common refrain in schools and in homes. The self-construction of adolescent youth, especially boys, as “bad” or “reluctant” readers is alarming at a number of levels—first, for those young people who have framed themselves in that way; and, second, for the societies they will enter and ultimately sustain. As such, creating a “culture of reading” across schooling contexts has been the subject of scholarship and international forums specifically dedicated to research and practice for literacy (Christenbury, Bomer, and Smagorinsky 2009; Power, Wilhelm, and Chandler 1997; Wilhelm 2008).

In terms of teaching English as a foreign language (EFL), the communicative language teaching paradigms that have long dominated the field tend to downplay literacy as a focus in preference for conceptualizing language as distinct if overlapping skill sets of reading, writing, and listening. Whether a student did or did not like reading has historically been of less concern to a field more focused on communicative language development. Yet, with more contemporary proponents of “literacy” arguing the multidimensional, multimodal, and existential ways of reading the “word/world” as an alternative (Freire 2000; Heath 1983; Paris 2011), the concept of literacy has slowly begun entering the professional lexicon of TESOL (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) International Association and other leading English language teaching professional organizations; in addition, the “power of reading” is an emerging centerpiece of primary and secondary curricular paradigms (see Fay and Whaley 2004; Krashen 1993).

In this article, we argue that how adolescent language learners position themselves as readers does matter to teachers of EFL and that teachers do not have to accept a student’s declaration of “I don’t like to read” as a permanent reality. Schools, and English language classrooms in particular, can promote a culture of reading that forwards a communicative paradigm and at the same time embraces literacy as a “system for representing the world to ourselves—a psychological phenomenon; at the same time it is a system for representing the world to others—a social phenomenon” (Barton 1994, 33).

Specifically, we outline in practical ways the potential of applied theatre for stimulating purposeful, creative literacy engagement with adolescent learners in order to engage communication in multiple modalities and in interactive ways. We begin with a brief overview of applied theatre and contemporary theorizations of its relationship to literacy development. We continue with a description of four approaches for activating applied theatre for literacy development, using Shel Silverstein’s (1964)The Giving Tree as an anchor example. We conclude with special attention to how applied theatre might be leveraged across grade levels in diverse classroom settings and adapted for varied genres and forms of text. Our intent is directed to practitioners with the message that bringing theatre into the language classroom can be more than a warm-up activity or an end-of-unit celebration for parents and siblings. Rather, applied theatre can engineer far deeper literacies that ultimately reposition reading as transacting with the wor(l)d.

Four moves for deepening literacy production

While the strategies we describe can be used with any number of texts, as a common thread we use The Giving Tree to illustrate the theatrical “moves” we advocate. Just as other literacy strategies can be adapted to suit context and content, these applications of theatre can be used with a wide range of texts for a multitude of purposes, in series or in isolation. The short narrative of The Giving Tree tells of the relationship between a boy and a tree. Initially, the boy embraces the tree as a playmate—climbing under its wide branches. However, as he grows into a young man, he begins asking the tree for pieces of itself—its apples, branches, and finally its trunk—until the tree is nothing more than a stump for an old man to rest on. All the while, the Giving Tree is “happy” if the boy-man is happy—regardless of the sacrifices she makes to satiate his needs.

Traditionally, reading a story such as The Giving Tree would be broken down into a series of print-based pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading activities that might include vocabulary review or vocabulary building exercises as a way of activating readers’ language schema in advance of the text; formative comprehension checks perhaps in the form of mapping out the narrative’s beginning, middle, and end; and, finally, some sort of summative comprehension check—often in the form of short written answers on paper.

As we will illustrate, applied theatre reframes reading as a creative transaction with meaning. These strategies can take verbal and non-verbal forms. They can be used in isolation or in combination. As such, readers are not looking for a fixed meaning within a text that they individually demonstrate their understanding of through a series of correct answers. Instead, literacy through an applied theatre lens frames reading as a recursive, collaborative, and generative transaction with meaning.

Like applied math and applied linguistics, applied theatre is eminently practical—with a primary focus not on distanced theories but on the immediacy of performance. Applied theatre can and should happen outside of traditional theatre spaces—whether that space is a school classroom, a library, a women’s clinic, an outdoor farmers’ market, a street corner—or just about anywhere. Breaking from traditional conceptualizations and enactments of performance, applied theatre values the dynamic, creative processes of embodied literacy embedded in day-to-day human activity and relations, with a focus on the process of creating. Whether it ends in a performance or not, applied theatre is in and of itself a generative act.

Because applied theatre has roots in the realms of both theatre education and popular theatre, many point out that though the term “applied theatre” is contemporary, its origins are ancient (see Prendergast and Saxton 2009). Indeed, communities and individuals have for millennia leveraged public performance to explore, express, and give meaning to individual and community experiences. Whether we are referring to Theatre of the Oppressed (Boal 1979), Brecht’s Learning Plays of the 1920s and 30s (Hughes 2011), or the rituals of ancient Greece and Africa, theatre has included practitioners dedicated to participant-centered forms in a range of contexts, sometimes including classrooms.

Research supporting and describing the links between applied theatre and literacy learning rests on this history and relies heavily on a growing base of case studies and practitioner-driven inquiry that help those inside and outside the field imagine the nuances of the communication context fostered by the union of drama and literacy. Theatre strategies mediate a space for generative, social meaning-making and response to literature (Schneider, Crumpler, and Rodgers 2006), scaffolding talk (Dwyer 2004), driving collaborative inquiry and problem solving across subject areas (Bowell and Heap 2001; Swartz and Nyman 2010), and shaping and informing writing (Grainger 2004). This context, reliant on the chemistry between leader and participants in equal part, is particularly effective for inspiring literacy growth among groups traditionally labeled “reluctant” or typically underserved by their system of education, including English language learners (Kao and O’Neill 1998).

Adolescent students in particular welcome the interplay of immediacy and distance in theatre as a way to negotiate complex identities between real and imagined worlds (Gallagher 2007). As students embody the theatrical space, they come to own the communication and shared context it fosters as well. In some settings, the theatrical mode echoes and honors familiar local cultural forms (Kendrick et al. 2006), creating an opportunity for deepening relevance.

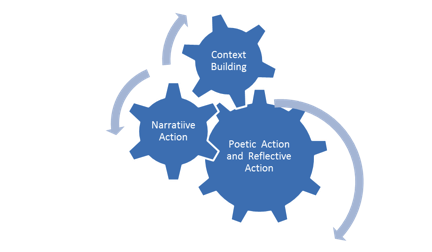

The four moves we describe (context building, narrative action, poetic action, reflective action) have much in common with the pre/while/after-reading sequence in that the moves are purposefully helping readers engage with the text at hand in scaffolded ways (see Figure 1, adapted from Neelands and Goode 2000).

Figure 1. Four “moves” for engineering deep literacy

There can be elements of story (beginning, middle, and end) inherent in an applied theatre approach to exploring a narrative, but when the approach is framed as a literacy process, the focus is on providing readers with multiple opportunities for meaning-making and symbolic representation of experience. In the sections that follow, we illustrate how the concept of applied theatre can become action. Blending ideas from the landmark drama/theatre compendium of strategies compiled by Neelands and Goode (2000)with contemporary arguments for textual enactments in middle grades and secondary-level literacy instruction (Wilhelm 2004, 2008), and incorporating our own shared experiences as theatre/literacy educators, we outline the concepts of context building, narrative action, poetic action, and reflective action as possibilities for the EFL classroom. Our intent is to create a direction for teachers interested in exploring the potential of process-oriented enactment strategies in fostering spaces for deep literacy engagement for reluctant adolescent readers.

Context building: Co-creating wor(l)ds

Applied theatre engages everyday people as “spect-actors,” where the line between actor and spectator/audience is purposely blurred. This approach fosters perspective taking that disrupts traditional power structures and interaction patterns such as teacher/student or performer/audience through embodied analytic communication (Boal 1979; Kao and O’Neill 1998). While some forms of applied theatre rely upon a degree of theatre expertise among facilitators or performers, the heart of applied theatre is of and for the common person. Applied theatre is home to trained artists and to regular folks with a continuum of approaches, contexts, and participants. Indeed, a tenet of applied theatre is its inclusion of and its connection to community, place, and participants. O’Neill (1995), a noted process drama scholar, points out that sometimes a strong theatrical sense helps applied theatre practitioners, and sometimes it is a hindrance. When the goal of the work is as much (or more) about inspiring, challenging, and framing the perspectives of participants as it is about performing art, seasoned theatre artists can struggle to let go of habits of traditional theatre performance that short-circuit responses to in-the-moment developments reliant on strong listening and observation. This is welcome news for novices, such as EFL classroom teachers, applying theatre in their context. No experience is required to begin.

Traditional plays center on the sequential performance of a scripted work; applied theatre centers on collective meaning-making and may or may not culminate in a final, polished performance in the traditional sense. Rather, creative explorations frequently progress more episodically than chronologically, with a heavy emphasis on participants inhabiting (and being challenged within) a range of perspectives, instead of enlivening a single character. Thus, an individual or group might simultaneously be asked to take on the perspectives of multiple characters—or even peripheral imagined characters to the story. In the case of The Giving Tree, spect-actors might be asked to take on the role of the tree or the boy or the tree’s imagined best friend—a little squirrel—or the boy’s cousin.

Sound-tracking texts

In process-based theatre, context-building conventions prepare participants for interaction with a specific text or idea as well as uncover or construct background and backstory. Theatre practitioners recognize that readers bring to texts “funds of knowledge” (Moll et al. 1992)or “schema” for transacting in dynamic ways with language, culture, and literacy. Sound-tracking is one such strategy. A collaboratively created soundscape helps participants build the world of The Giving Tree aurally as a way to activate prior knowledge and imagination. Before sharing the book with students, the teacher has them brainstorm a list of words to describe a child-friendly forest where trees care for people and people care for trees. What are the sounds of this forest? What are the primary sounds? The subtle sounds? Are there words? Are there voices? Have students suggest options and try them out, slowly building a one-minute soundscape using the class as the sound chorus, pausing for feedback and revision from the whole group, then circling back to incorporate ideas. We encourage teacher-facilitators to limit sound-making options to student voices and sound-making movements (e.g., whistling like a bird or gently tapping on a wooden desk in a way that might evoke rainfall) to foster innovation and focus problem solving.

Freeze-framing the written word

Having students use only their bodies and each other to create images in response to challenges creates opportunities for collaboration and communication physically, verbally, and non-verbally. To get at comprehension, we have leveraged something we like to think of as “freeze-frame reading”—an activity that blends kinesthetic and visual intelligences by challenging participants to use their own bodies to create a frozen image of a textual moment or key concept. The activity typically begins with a shared reading of a short text or passage (fiction or non-fiction), followed by an identification and discussion of a key moment in the narrative or an important concept. The Giving Tree provides readers with multiple opportunities for freeze-frames. Freeze-frames allow participants to identify and embody a specific narrative moment of the relationship between the boy and the tree or a complex concept such as “generosity.” Still images can also be used to help participants flesh out and share inferences about a setting, a relationship, a history, or a lifespan.

Students, in groups of three or more, might also create with their bodies a single frozen frame to illustrate a key contextual moment or concept. Allow groups time to brainstorm and rehearse. Share with the group at large. While each group is frozen, prompt the onlookers for analysis with questions like these:

- “What do you see?”

- “What relationships are here?”

- “If you had to give this image a title, what would it be?”

- “What might this person be thinking or saying?”

Stress to participants that the freeze-frame is frozen. Only the observers can talk. After each group’s “performance,” give the frozen group a brief opportunity to explain their intentions, qualifying that this is different from charades because there is no specific correct answer. In the prompt, students can be charged to create specific kinds of still images as it suits the larger drama, such as surveillance camera stills, photos from an album, or an advertisement.

Narrative action: Moving the story forward

Narrative conventions help participants build the emerging drama’s plot. This is not the same as dramatizing an existing story; rather, it involves enacting some elements, but also extending and elaborating ideas only hinted at in the text, implied in the illustrations, or imagined by participants. Narrative strategies are recursive and fluid but always build meaning.

Expert meetings about content and issues

Endowing the participants with expertise (power, high status) and the leader with a problem requiring assistance (need, low status) turns the hierarchy of the classroom on its head and prompts participants to speak and think and share and listen (Heathcote and Bolton 1995). Let’s say that the adolescents reading The Giving Tree are part of an imagined community conservation alliance—they are responsible for taking care of the trees but even more for protecting the environment for future generations. The teacher, in role as a new assistant to a local government official, initiates a conversation soliciting ideas, framing the children as experts—an arborist, a scientist, a farmer, a park ranger—and asking them to formulate their expert opinions about why trees are disappearing or abused and what possible actions should be taken.

Initiating an “expert meeting,” the teacher, out of role, explains that (1) there will be a meeting, and the students will be playing roles of people concerned with trees; (2) the teacher will take on a role, too; and (3) everyone must work together to improvise possibilities.

Some groups benefit from brainstorming a list of possible expert roles, but we caution against assigning everyone a role. Let them choose as the meeting evolves. Some will make strong character choices, others remain closer to themselves, and still others simply observe. All are valid ways to participate. The meeting itself need not be longer than a few minutes. Some teachers opt to wear a small costume piece to differentiate between themselves when they are in and out of role. It is helpful to think about the teacher as fostering possibilities rather than answering questions: opening up, not closing down. The meeting can close with the promise of future contact. This is a beginning, not an end.

Interview pairs about main and peripheral ideas

After students form pairs, one student interviews the other. One person in the pair is from the committee or is a reporter, and the other a community member who knows something about the situation. To support those students tentative about language, decide on a few stock questions (“What is your name?”; “How or what do you know about [global warming]?”), and then generate a common list of possible interview subjects and share possible questions for specific interviewees.

For The Giving Tree, interview subjects might include the park ranger, an elderly woman who lives at the edge of the woods, a political activist, or a talking rock. The pair engages in a brief, scaffolded interview, perhaps two minutes long, in which one partner questions and the other answers to build background information. All pairs are interviewing in parallel. There is no audience. After the interviews, the interviewer reports his or her most interesting finding to the class. An emerging student might simply read aloud a written response to the interview questions that his or her classmate has recorded on paper. An advanced student may speak as if reporting on the television news.

Hotseating characters and readers

Hotseating is essentially a group interview (interrogation) of one person. Hotseating and interview pairs are the same at their heart, with different stakes. The public nature of being interrogated on the hotseat by a crowd differs qualitatively from chatting one-on-one with a reporter in a quick interview. The context can be framed as a hearing or a media interview. If The Giving Tree drama work continually points to a person who has a significant hand in or a significant insight into the deforestation issue, he or she might be a worthwhile hotseat candidate: perhaps the boy or perhaps the Giving Tree will be recommended. Challenging the group to hotseat a role not fleshed out in the text creates a degree of creative freedom and challenge. Generating strong hotseat questions both as a group and individually prior to assigning the hotseated role improves the quality of questions and prepares those to be interrogated.

He said/She said

One example of a scaffolded hotseat is something we call “He said/She said.” This narrative strategy asks participants to assume the role of a character in a text—or an implied character—and to explain his or her point of view and subsequent rationale for his or her actions. With The Giving Tree, participants might, for example, assume the role of the tree or the boy—or an imagined character, such as the boy’s grandparents or a squirrel—and be called before what might be termed the “Forest Council.”

Again, students form small groups, this time prepping a participant to play a role with talking points for a brief “opening statement” explaining the rationale for or—depending on the role—their perception of a character’s actions. For example, the boy’s opening statement might narrate a childhood tragedy that left him completely dependent on the tree. The tree’s opening statement might describe her ideas about generosity and how it was that she came to feel so responsible for the boy’s happiness. A peripheral character such as a squirrel might describe his or her feelings about seeing the tree destroy herself.

After the series of opening statements that might include a “counter narrative” of the boy-man justifying his actions or grounding his dependency on an imagined background story—for example, he was orphaned as an infant and his father and mother had entrusted his well-being to the tree—the characters engage in a question/response session (hotseat) with the class. You can opt to use the introductions to segue into hotseating for each role, or you can have the group vote on which two perspectives they want hotseated, based on the introductions.

Poetic action: Representing and symbolizing structures and concepts

Many theatre-based explorations with young people include narrative-action and context-building elements, stopping short of the deeper elements fostered by poetic action and reflective action. Poetic strategies challenge participants to work on the symbolic and abstract levels with “highly selective use of language and gesture” (Neelands and Goode 2000, 6). While language and gesture contract to become focused and spare, the context in terms of time and space frequently expands to foster broader, deeper inquiries and insights and complex perspectives. In other words, as readers engage in a text, representing and symbolizing push student spect-actors to ask themselves what the text means for their lives—its potential implications and applications for who they are and who they are becoming. Thus, “poetic moves” encourage readers to think about decoding text as a creative act—not merely figuring out what the text means at the word, sentence, or discourse level, but what it could also mean symbolically for their specific contexts.

Forum theatre: Public re-vision

Forum theatre, a convention originating from Boal (1979), functions just as it sounds. A small group of spect-actors depicts a carefully selected challenging scene or situation while the remaining spect-actors look on. However, the wall between actors and observers is permeable, and actor or observer can stop the action at any point to share any insight, ask a question, or even replace an actor with an observer. The scene is replayed, interrupted, problematized, and analyzed several times with the goal of possibility and exploration as an aim, not just performing a “good scene.”

To begin, choose two actors to be the boy and the Giving Tree in their old age. Have them play out the story as written. Discuss with the entire group how some readers consider that this is a story about sharing; other readers see it as about selfishness. Explain that the actors are going to replay the story and, at any point, you or they can call “freeze” to stop the action. Challenge the audience to find stopping places where a different course of action could be taken if different choices were made or different circumstances were in place. Perhaps share a limited example to demonstrate the logistics, but be careful not to simply replay a different story with a plot dictated by the leader. Be ready with questions like, “What other options does the tree have here?”; “What about the boy?”; “Would intervention by another character change the story?”; and “What other events could occur and impact the story?” The discussion among the forum at these stopping places is even more important than the acting out of the story. Remember, a member of the forum can share an idea for the current actors to enact, or a member of the forum can replace an actor, bringing a new dimension and voice to the evolving scene. Finally, reflect individually and collectively on these new choices and endings and their messages. This reflection might be done in the form of a sharing circle—with participants simply voicing their ideas—or on paper in small groups with a representative sharing the group’s combined short reflection.

Flashback/Flashforward: Narrative points of view

Purposely playing with time helps break students out of the narrative mindset. Asking them to construct scenes, stories, or still images across a broad spectrum of time does include a narrative element, but it also challenges participants to boil down and focus their art. Taking away the verbal element can heighten the art as well as scaffold communication across language borders.

For The Giving Tree, a poetic exercise might take the form of having the adolescents imagine it is now 50 years after the tree’s death. They have been commissioned to create a wordless, musical video tribute to honor the history of the forest where the Giving Tree lived. Select a piece of music that is one minute long and have the adolescents form groups of three to five and choreograph a wordless scene from the history of the forest to perform for the entire class and then craft into a whole. Or, if the group wants to enter physically first, the teacher might ask the class to make a forest using their bodies—and then to embody that same forest in some sort of danger of extinction or destruction.

Reflective action: Looking forward, backward, and inward with texts

Reflective conventions stop the action and ask participants to “stand aside . . . and take stock of meanings or issues that are emerging” (Neelands and Goode 2000, 75). Participants are prompted to reflect, look back, or take a stand. Traditionally, having participants reflect on their learning happens as a means of closure in a well-planned lesson. We argue that theatre-centered strategies for bringing individual and group closure add layers of reflection to discussion and naturally meld disparate perspectives into a multi-voiced unit or experience. Moreover, the reflective strategies we describe in this last move make individuals’ learning public and provide the teacher-facilitator with valuable summative feedback about what an adolescent or a group took away from embodying a text.

Tapping into readers’ reactions

Have students take a place in the room to collect their thoughts. Explain that the leader will circulate and tap each person on the shoulder. When tapped, each participant will speak a word, phrase, or sentence that describes a vivid insight, feeling, or observation they had about The Giving Tree during the various performance “processes.” That might sound something like “Greed”; “Generosity can be destructive”; or “I’ll think before I ask for something—what my asking or taking might do to the other person.” For large classes with a range of language abilities, a variation on “tapping in” might include having clusters of students first form groups to discuss and record their reflections on paper. The clusters might then collectively embody some aspect of the mythical forest they depicted in the earlier learning segments with the teacher-facilitator tapping in not on individuals but on groups—with one or two group representatives articulating some of the reflections that members of the cluster voiced in the group reflection session.

Spaces between characters’ motivations and rationales

After a session where the relationship between the boy and the Giving Tree is prominent, have two volunteers stand before the group, one representing the boy, the other representing the tree. Ask another volunteer to place the two in relationship to each other, with the distance between the two telling us something important about their relationship. Ask the volunteer who just placed the boy and the tree to explain or interpret the physical space between the two characters. This might sound something like, “The space between the boy and the tree is about how the boy only thinks about himself and never the tree. The tree wants them to be closer—but the boy is always leaving. That’s why the boy is far away from the tree.” Let the group comment and question. Repeat with others placing and explaining.

Corridors of readers’ responses

Have the students imagine they are the collective conscience (or the thoughts) of the future generation of the Giving Tree’s forest. Explain to students that they will create a “human conscience hallway” with students facing each other about a meter apart in parallel rows. Each thinks of one piece of advice, one nagging question, or one cautionary phrase he or she wants the future generation to have in mind. Have a student walk through the human conscience hallway slowly as each student repeatedly says his or her chosen phrase. If time permits, have each participant take a turn walking through the conscience hallway.

Branching beyond The Giving Tree

We used The Giving Tree as an anchor text to help practitioners imagine specific strategies in action with a familiar text. The danger of aligning these strategies with a specific text, of course, is that readers start to see the strategies tied only to one story. It is important to remember that these strategies can be adapted to a wide range of texts. Traditional folklore, written or oral, pairs well with applied theatre strategies. In many ways, The Giving Tree echoes a folkloric style with its simple plot, elements of repetition, two-dimensional characters, and clear intended moral. The features entice participants to fill in, flesh out, and question the simple text. The story becomes the springboard for complexity through theatre. Adolescents find comfort in the familiar tales of childhood and freedom in twisting them into a new direction. Through soundscape, the context of a forest or a jungle or a kingdom or a market square can be enlivened in any classroom. Similarly, hotseating a character who has made errors, committed crimes, or acted selfishly positions spect-actors to flesh out two-dimensional characters with nuanced, justified motivations; the same is true of forum theatre. Further, finding traditional stories that are part of a community’s culture creates opportunities to purposefully connect with local lore and resources. If there is no written text of the story available, then collecting, listening to, retelling, illustrating, and sharing local stories adds another culturally relevant layer to your literacy environment. Just be mindful to choose stories without strong religious or spiritual parameters to “play” with—there are always many.

The anchor text you work from could be any genre, from fiction to non-fiction to poetry—even an illustration or photograph. You can use all or a portion of the text. You can use theatre strategies before, during, or after the full reading or examination of the text. However, some texts lend themselves more to the generative nature of applied theatre than others. Here are some questions to ask yourself as you filter texts for applied theatre possibilities:

- What are some multiple perspectives (written or implied) this text affords?

- What are the relationships and tensions that invite unpacking or extending?

- Are there “unseen scenes” or peripheral incidents worthy of exploration?

- Whose are the marginal voices that could be heard through dramatic activity?

- What are the hard-to-answer ethical questions this text evokes?

- What are the assumptions and easy answers that theatre could productively muddy?

The important step is to begin with a text that captures your interest and take a few small risks, then reflect and refine for the next episode. You will have many ideas, but the student work will suggest ideas and directions you had not imagined. Allow yourself time between installments to take in student ideas, mull them over, and build on them. As you grow in comfort applying theatre, you will be more able to do this on your feet. Your students’ positive response and their newfound voices brought forth in these authentically situated contexts will inspire your planning as well.

Conclusion: Performing literacy in classroom contexts

In making reading about more than decoding words on a page, EFL teachers and teachers of drama and theatre find common ground to push back against students framing themselves as reluctant or bad readers. Using applied theatre strategies helps teachers across disciplines stretch the multimodal and cultural borders of literacy to embrace multiple pathways to and through meaning-making that include traditional reading, writing, and listening facets within a broadened view of classroom communication covering an embodied semiotic system.

In other words, applied theatre creates opportunities for expressive and receptive communication in audio, gestural, spatial, linguistic, and visual modes working together in a complementary way (Cope and Kalantzis 2000). This effort makes space for diverse students to find entry points into the material. It also values adolescents in the co-construction process. Remember that teachers can start small, using a single strategy, or opt to string several strategies together in a single session or across a unit of instruction. Though the goal of this work is not performance, many teachers find that the material and excitement generated by students in a literacy-cum-applied theatre setting can be shaped into a sharing/performance event celebrating literacy and the meaning-making transaction that reading can be.

References

Barton, D. 1994. Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Boal, A. 1979. Theatre of the oppressed. New York: Urizen Books.

Bowell, P., and B. S. Heap. 2001. Planning process drama. London: David Fulton.

Christenbury, L., R. Bomer, and P. Smagorinsky, eds. 2009. Handbook of adolescent literacy research. New York: Guilford.

Cope, B., and M. Kalantzis, eds. 2000. Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Dwyer, P. 2004. Making bodies talk in forum theatre. Research in Drama Education 9 (2): 199–210.

Fay, K., and S. Whaley. 2004. Becoming one community: Reading and writing with English language learners. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Freire, P. 2000. Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th anniversary ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic. (Orig. pub. 1970.)

Gallagher, K. 2007. The theater of urban: Youth and schooling in dangerous times. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Grainger, T. 2004. Drama and writing: Enlivening their prose. In Literacy through creativity, ed. P. Goodwin, 91–104. London: David Fulton.

Heath, S. B. 1983. Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heathcote, D., and G. Bolton. 1995. Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hughes, E. 2011. Brecht’s lehrstücke and drama education. In Key concepts in theatre/drama education, ed. S. Schonmann, 197–201. Boston: Sense.

Kao, S. M., and C. O'Neill. 1998. Words into worlds: Learning a second language through process drama. Stamford, CT: Ablex.

Kendrick, M., S. Jones, H. Mutonyi, and B. Norton. 2006. Multimodality and English education in Ugandan schools. English Studies in Africa 49 (1): 95–114.

Krashen, S. D. 1993. The power of reading: Insights from the research. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice 31 (2): 132–141.

Neelands, J., and T. Goode. 2000. Structuring drama work: A handbook of available forms in theatre and drama. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Neill, C. 1995. Drama worlds: A framework for process drama. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Paris, D. 2011. Language across difference: Ethnicity, communication, and youth identities in changing urban schools. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Power, B. M., J. D. Wilhelm, and K. Chandler, eds. 1997. Reading Stephen King: Issues of censorship, student choice, and popular literature. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Prendergast, M., and J. Saxton, eds. 2009. Applied theatre: International case studies and challenges for practice. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Schneider, J. J., T. P. Crumpler, and T. Rodgers. 2006. Process drama and multiple literacies: Addressing social, cultural, and ethical issues. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Silverstein, S. 1964. The giving tree. New York: Harper and Row.

Swartz, L., and D. Nyman. 2010. Drama schemes, themes and dreams: How to plan, structure, and assess classroom events that engage young adolescent learners. Markham, Ontario: Pembroke.

Wilhelm, J. D. 2004. Reading is seeing: Learning to visualize scenes, characters, ideas, and text worlds to improve comprehension and reflective reading. New York: Scholastic.

—––. 2008. “You gotta BE the book”: Teaching engaged and reflective reading with adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

BIODATA:

Beth Murray, PhD, is Assistant Professor of and coordinates the program in Theatre Education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Years as a public-school theatre teacher, a teaching artist, a program development facilitator, and a playwright/author for young audiences undergird her current research and creative activity.

Spencer Salas, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary, and K–12 Education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Michele Ni Thoghdha is the Chief Supervisor for English with the Ministry of Education, Oman. Prior to her current position, she has worked as a teacher, teacher trainer, supervisor, and department head in various countries. Her areas of specialization are young learners, development drama, and literacy.

Format: Text

International Subscriptions: English Teaching Forum is distributed through U.S. Embassies. If you would like to subscribe to the print version of English Teaching Forum, please contact the Public Affairs or Cultural Affairs section of the U.S. Embassy in your country.

U.S. Subscriptions: English Teaching Forum is exempted from the Congressional restriction on distribution of Department of State-produced materials in the United States. U.S. residents who want to order the printed edition can order from the U.S. Superintendent of Documents.

One of the greatest joys for teachers is to be able to inspire a love of teaching in their own students. Having students tutor other students is one way to accomplish this. A well-planned and carefully organized tutoring program can lead to remarkable gains for tutors, tutees, and teachers.

While starting a tutoring program may seem like a daunting and time-consuming task, it does not have to be. The best way to approach the creation and development of a tutoring service is with a list of clear objectives. In this article, I describe the process I used to create a tutoring program with my English as a foreign language university students. I identify questions that need to be addressed at each step of the program development process, then explain how my student tutors and I answered these questions.

The answers that shaped the final program were specific to our situation and location; however, if I had been in another location with different students and resources, the same questions would have led to different answers—and a different program. But it would have been a program tailor-made to fit the needs of the student tutors and the tutees. Thus, the only “right” answers to these questions are the ones that are “right” for each teacher’s time, place, and students.

What is tutoring?

It is perhaps best to begin by looking at an explanation of what tutoring is and what benefits it provides to both the tutors and their tutees. Peer tutoring, also known as peer-assisted learning, is defined as “the acquisition of knowledge and skill through active helping and supporting among status equals or matched companions” (Topping and Ehly 1998, 1). It can incorporate everything from teaching, mentoring, and counseling to behavior modeling. Much of the research on peer tutoring is overwhelmingly positive (National Tutoring Association 2002). Peer tutoring has been studied in multiple settings and with many types, ages, and levels of learners, including (but not limited to) children, teenagers, second-language learners, and autistic learners. It has been studied with a variety of subjects, from biology and mathematics to physical education.

The positive benefits are numerous and significant. Topping and Ehly (1998) note that “tutors can learn to be nurturing toward their tutees, and in so doing, develop a sense of pride and responsibility” (4) and that improved motivation and attitude can lead to “greater commitment, improved self-esteem, self-confidence, and greater empathy with others” (13–14).

But tutoring leads to gains in more than self-esteem and empathy, important as these are. Research indicates that students who tutor others also make significant academic gains (National Tutoring Association 2002; Topping and Ehly 1998; Galbraith and Winterbottom 2011; Fantuzzo et al. 1989; National Education Association 2014). In their study of peer tutoring, Galbraith and Winterbottom (2011) report that “tutors’ perceptions of their role motivated them to learn the material, and their learning was supported by discussion and explanation, revisiting fundamentals, making links between conceptual areas, testing and clarifying their understanding, and reorganizing and building ideas, rehearsing them, and working through them repeatedly, to secure their understanding” and that “mental rehearsal of peer-tutoring episodes helped them appreciate weaknesses in their own subject knowledge” (321).

It is important to be aware that, while this article focuses on a program that was created to provide teaching experience to pre-service English teachers, anyone can tutor—and anyone can be tutored. Tutors can be almost any age, from primary school up, and they can come from a variety of different disciplines and specializations. Ten-year-olds can tutor six-year-olds. Biology students can tutor others in biology. Accountants can tutor in business. The benefits to tutors and tutees are similar regardless of the field in which they are working.

How to develop a tutoring program

The following seven steps serve as a guide to plan, develop, and initiate a successful tutoring program.

Step 1: Determine the needs of both the tutees and tutors and design a program that meets them

My first questions were about the tutees, the people my students would tutor. I needed to determine the following:

- Who (and how old) will the tutees be?

- Do they need homework help, conversation practice, assistance in writing, or listening practice?

At this stage in the process, it is essential to be aware of local beliefs about education. For example, although peer-tutoring programs are common in the United States, in the culture where I was teaching, university students are reluctant to accept instruction from their peers. Thus, it was best for my students to work with younger, school-aged children who were learning English, and the program became a cross-age tutoring program focused on having tutors use communicative language teaching methodology to provide homework assistance.

Secondly, I had to think about who the tutors would be and what their own needs and goals were. I had to consider:

- What experience do the tutors need?

- Do they need opportunities to work with children, teenagers, adults—or learners of all ages?

- Do they need opportunities to lead classes or groups, or can they focus on one-on-one tutoring?

In my students’ cross-age tutoring program, they would be teaching children with a rather basic level of English. Would this be enough to push their own development of English? Kunsch, Jitendra, and Sood (2007) note that cross-age tutoring, where students have different levels of expertise, is a successful approach. In addition, research on cross-age tutoring indicates that tutors working with younger learners experience gains similar to those of peer tutors in the areas of empathy, confidence, and self-esteem (Yogev and Ronen 1982; Hill and Grieve 2011). Tutors still need to understand English well enough to explain it clearly to younger learners, even if they are using the students’ first language. In fact, clarity of explanation would be vital, as children have fewer metacognitive or coping strategies to resort to if they do not understand something.

My next question was, “Who should tutor?” I did not want to make being a tutor mandatory for all my students. I also wanted the service to be free for the children, meaning that the tutoring would not generate any income and that I would not pay my tutors for their work.

I also asked myself what criteria I should set for selecting my tutors. Should I allow only my students with the highest levels of English to tutor? What role should a student’s responsibility, motivation, and initiative play in my decision regarding who should tutor? In the end, I opened the program to all my students and presented it as a unique volunteer opportunity that would look impressive on a curriculum vitae (CV). I also talked to students about the benefits of tutoring—how it would not only give them teaching practice, but also help them improve their English.

It is important to remember that tutors do not need to be experts in what they are tutoring; they can be in the process of learning the material. After my tutors had been tutoring for several months, I asked them what qualities a tutor should have. They responded that tutors should be interested in helping people, open to learning about their tutees and trying different techniques and ways to connect with them, and able to explain difficult concepts in simple, easy-to-understand language. Even the tutors themselves recognized that it is not necessary for an effective tutor to have advanced English proficiency.

Step 2: Consider what resources are available

Try to answer the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “when” questions about available resources to identify what you have and do not have. Some things to consider include:

- Who is available to observe and assist the tutors and provide feedback?

- What books and materials are available for the tutors to use?

- What other resources (e.g., computers, whiteboards, markers, desks, classrooms, Internet access) are available?

- Where can the tutoring sessions be held?

- When is the best time to hold the tutoring service?

For a new program, the ideal situation is one where the program can build on the popularity of a similar service. In our case, the local American Center was already offering English conversation classes to school-age children on Saturday afternoons, so it made perfect sense to arrange our tutoring service to coincide with their classes so that children could come early, receive homework help, and then stay for their conversation class. The American Center staff found a room to use for the tutoring and also made announcements to the children in their conversation classes.

Of course, not all teachers are as lucky as I happened to be—but, as my tutors became fond of telling people, all you really need for a successful tutoring session are a tutee, a pencil, and some paper. Tutoring can happen in any space and at any time. The most important aspect is the interaction between tutor and tutee, and that can happen anywhere.

One extremely important resource is other teachers who might be interested in helping develop and run a tutoring program and providing support to tutors. In fact, a group of teachers can divide the various tasks of recruiting tutors, training tutors, and advertising the program. But even if there are no other teachers who are available to help set up and run a program, as the tutors become more experienced, they will be able to take on more and more responsibilities. In fact, this model worked well for us because it helped the tutors become self-sufficient and built their confidence and self-esteem.

Also, as the tutors became more experienced, they were able to develop their own materials. After a few months, there was a cabinet full of teaching aids that the tutors had collected or created on their own initiative.

Step 3: Develop a training program that is tailored to the context

Again, look at who the tutors are, who the tutees will be, and the type of tutoring program you are planning. Different situations will require different information in training sessions to reflect the needs of the tutors. Skills-focused tutoring (such as writing, speaking, reading, or listening tutoring) will require different training than tutoring focused on providing homework help. Training can include information on any of the following areas, among others:

- methods of language teaching

- classroom management and behavior management

- child psychology and development

- error correction

- learning preferences and communication styles

Although creating a training packet can be a time-consuming task, it needs to be done only once, and teachers developing a training packet can ask other teachers for their input and assistance. In developing a tutor-training program, teachers can mine numerous resources available on the Internet and in teaching methodology books as they search for training materials. The Internet resources listed in the Appendix can help. Some of the resources listed (for example, the Anoka-Ramsey Community College Tutor Training link) are complete tutor-training modules including readings and assignments. Teachers who have limited time to create a tutor-training program from scratch can have their tutors complete the training modules from this site or others. Again, the approach depends on the needs of the teachers, tutors, and tutees, and on the resources available. Personal teaching experience can also be part of the training materials; in fact, it might be the most valuable of all resources. An experienced tutor can be treated as a resource and should be encouraged to share tips and techniques with new tutors.

The training packet that I created contained lessons on effective tutoring techniques, communication skills (including active listening), and ways to correct errors. Because finding time for training sessions was difficult, tutors were required to complete the training packets outside the training sessions by working with a partner. Each training session consisted of a review of the work the tutors had done, and the last ten minutes were used to set up the next tasks and answer questions about them. The system worked, especially when the tutors realized that if they did not complete the tasks, they would not be allowed to work as tutors.

The most important parts of any tutor-training program include practice tutoring, observations, and tutor self-reflection. Teachers should provide new tutors with the opportunity to practice tutoring, preferably with more-experienced tutors; teachers should also observe new tutors at least once and invite tutors to reflect on what went well (and what they could improve) in their tutoring sessions.

Step 4: Recruit and train tutors

This step goes back to the question of who the tutors will be. It is not always necessary that tutors be pedagogy students; remember, they will be provided with the necessary training for successful tutoring. In terms of the hiring process, questions to consider include the following:

- Should prospective tutors submit CVs and/or undergo interviews?

- What are the specific hiring criteria?

- What level of English do the tutors need to have?

- What other criteria will there be in terms of responsibility, maturity, and communication skills?

I wanted to make the tutoring service as professional as possible and to emphasize the importance of making a commitment. Thus, I required that students submit a CV if they were interested in being tutors. How to write a CV was something we had studied in class, and therefore asking potential tutors to submit CVs was a practical extension of that lesson. I also asked them to write a letter of motivation explaining why they wanted to be tutors. When selecting tutors, I focused on students’ level of interest in tutoring, interpersonal skills, and awareness of what tutoring is and what would be expected of them. Of course, while I considered these qualities to be important for the program I was starting, each program will be different, and thus the criteria for tutors should be different. Ultimately, the criteria for tutors will depend on the program objectives. Motivation, however, is an important quality for program success and sustainability.

Step 5: Advertise the tutoring program

After the tutors have been recruited and trained, it is time to advertise the tutoring program. Work with the tutors to spread the word about the program. Tutors can develop flyers and promotional materials. They can also contact local schools and universities, local English teachers, and English teacher associations; post information about the tutoring service on Facebook and other forms of social media; and encourage people to tell their friends and relatives.

Again, here is where it is useful, when possible, to build connections with other services that are already well known. Initial advertising can be conducted through word of mouth, which was what we did. Once the tutors became experienced, they wanted to advertise the program to a wider audience, and they created a trilingual brochure that included a map showing our tutoring location. They distributed the brochure to parents, English teachers, and children.

Of course, in advertising a free tutoring service for children, there is a danger that demand will outstrip the number of available tutors. When we faced this problem, the tutors took a vote and decided to extend their hours. They also decided to recruit and train additional tutors.

Step 6: Begin the sessions

After recruiting and training, we were ready to start. At this stage, observation, supervision, and feedback are critical to building a strong program. This is worth emphasizing, even if only one teacher is available to provide support to student tutors.

For our first tutoring session, I had the tutors work in pairs, with one tutor doing the actual tutoring and the other observing the session. After the tutoring hour ended, I invited the tutors to share their experiences, observations, and comments and suggestions.

The next tutoring sessions went extremely well. As my tutors worked with the children, I walked around and observed, making notes so that I could offer praise and suggestions. After each tutoring hour, the tutors and I would meet and discuss the sessions as a group. After several sessions, I encouraged the tutors to write a list of rules that would help them deal with the situations that they had encountered. One rule that the tutors felt was important was that parents had to wait outside the tutoring room (otherwise, the parents had a tendency to try to control the tutoring session). Tutors also agreed upon a strict first-come, first-served rule.

Step 7: Expand the program and build self-sustainability

One of the most exciting aspects of a tutoring program is that it provides tutors with opportunities to become leaders and coordinators. A tutoring program will be self-sustainable if tutors take on the responsibility of running and promoting the program, recruiting and hiring new tutors, training new tutors, and continuing to provide feedback to each other. Think about what “officers” are needed to run the tutoring program. Should there be an attendance coordinator? A recruiting and training coordinator? A general coordinator?

Sustainability and growth are important parts of any tutoring program and should be considered even while the program is first being developed. In our situation, I wanted to ensure that the tutors would have the skills and knowledge they would need in order to run the service without me. Also, the majority of my students had never been given any opportunities to lead. I saw in several of my tutors the potential to successfully take on greater responsibility for the program, so I divided the work I was doing for the tutoring service into separate leadership roles and wrote descriptions for each. I decided that the service would need the following: an attendance coordinator to track both tutor and schoolchild attendance; a secretary to take notes at meetings, send out email notifications, and keep track of our resources; a community liaison to promote the service, write grants, and build relationships with local teacher groups; and two hiring and training coordinators.

When the tutors returned from winter break, we held elections to select their new leaders. I immediately gave a stack of new CVs to the hiring coordinators, and we discussed criteria for hiring new tutors. The experienced tutors took charge of hiring, training, and mentoring. The tutors expressed doubts about their readiness to completely take over the service, but as it turned out, they were more than capable of doing so. Six months after I left (and a full year after the tutoring service had begun), the tutors had 70 tutor applications, from which they hired 17 new tutors. As Aydan, one of the leaders of the program, wrote, “Among the new tutors we have diplomats, translators, students from international relations, and others. They have so much desire to work, to help. I hope that this desire will stay with them for a long time.”

What we learned

As a teacher, I learned that a tutoring program leads to previously undreamed-of opportunities for both teachers and tutors. For example, the tutors I worked with were invited to give a presentation at a conference of English teachers in a neighboring country. This conference was, for many of the tutors, the highlight of their tutoring experience. Several of them had never been out of their country before, and none had ever delivered a presentation outside their classes. And yet there they were, standing in front of more than 100 English teachers, talking about the work they had been doing as English tutors.

Although this exact opportunity might not be available to everyone, there will be others. One way to motivate tutors is to connect them to local English teachers’ associations. Perhaps tutors can volunteer at local conferences in exchange for the chance to attend the conferences for free. Tutors can organize classes, festivals, or field trips for their tutees—the possibilities are endless. The main thing is to search for and be open to new ideas and possibilities.

I recently asked my tutors what they had learned from their tutoring experience. While I had expected a positive response, I was taken aback by how much self-awareness and insight their responses showed. Without my having prompted them, several tutors mentioned the same benefits that the researchers cited above had found.

One tutor, Sakina, in responding to my question, said, “Actually tutoring service is not that common in our home country, but implementing this project is really very useful for both the tutors and the students.” Another tutor, Aygul, said, “Tutoring allows you the opportunity to develop intellectually, psychologically, and personally. Tutors mature and gain self-confidence as they work. […] It reinforced my ability to communicate clearly, logically, and creatively.”

Of course, we all learned the importance of remaining flexible, particularly in the early stages of the project. Tutors who were involved from the beginning were able to observe how such a program was designed and developed. Another lesson was the importance of using experienced tutors as resources—not only for hiring and training, but also for the daily operations of the tutoring program and even in the creation of tutoring materials.

For myself, I learned that motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, is (almost) as good as money—though the tutors certainly looked forward to the baked goods and treats I would bring each week. And while there was one tutor who decided to stop tutoring due to family reasons, the other tutors stayed with the program all year. I attribute this dedication to the fact that they were all highly motivated and found the tutoring experience rewarding and enjoyable.

To help with tutor retention rates, I learned that it was important to provide additional support for tutors with weak language skills. In receiving this support, tutors felt more qualified to teach and at the same time appreciated the opportunity to improve their English. As a tutor named Narmin said, “Tutors and tutees get benefits from this program. We tutors improve ourselves a lot. Sometimes we meet some words which we have forgotten, then we ask one another or look through a book. In this way we learn, too.”

Final thoughts

It is my hope that in detailing the process that I went through, this article can serve as a guide to others who wish to create similar programs. Again, my goal is not that other teachers will create exact replicas of my program; rather, it is that others will use this article and the framework of questions to create their own individualized programs. The questions in Figure 1 can be used as a starting point for discussions with colleagues—and I highly recommend that English teachers work together to divide the work of starting a tutoring program. I have also included a list of online resources in the Appendix that can be consulted in order to create a personalized training manual for tutors in either a peer-tutoring or cross-age tutoring program.

|

How to Start a Tutoring Program: Questions to Consider

|

Figure 1. A framework of questions to consider when starting a tutoring program

Creating a tutoring program was hard work, and there were many challenges along the way, but the result was more than worth the amount of work that went into the program. The tutors have developed not only a love of teaching but also a greater sense of self-worth. They have come to see themselves as coordinators and leaders. The children who come for help look up to the tutors and often greet them with hugs and big smiles. The tutors take their responsibilities to these children very seriously. They have developed their own techniques for facing challenging situations, some of which reveal amazing insight into teaching and learning. The tutors feel comfortable experimenting with techniques, and they often make their children stand and move, or use colored markers, or sing songs, or watch and respond to short videos.

That the tutors embrace communicative and interactive teaching methodology is especially impressive—and critical—in a society where rote memorization and teacher-centered classrooms are still the norm. Perhaps it is because they are still students themselves that they are able to connect so closely with the children they work with, but whatever the reason, these amazing young tutors all have bright futures as English teachers and as leaders.

References

Fantuzzo, J. W., R. E. Riggio, S. Connelly, and L. A. Dimeff. 1989. Effects of reciprocal peer tutoring on academic achievement and psychological adjustment: A component analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology 81 (2): 173–177.

Galbraith, J., and M. Winterbottom. 2011. Peer-Tutoring: What’s in it for the tutor? Educational Studies 37 (3): 321–332.

Hill, M., and C. Grieve. 2011. The potential to promote social cohesion, self-efficacy and metacognitive activity: A case study of cross-age peer-tutoring. TEACH Journal of Christian Education 5 (2): 50–56.

Kunsch, C., A. Jitendra, and S. Sood. 2007. The effects of peer-mediated instruction in mathematics for students with learning problems: A research synthesis. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice 22 (1): 1–12.

National Education Association. 2014. Research spotlight on peer tutoring: NEA reviews of the research on best practices in education. Washington, DC: National Education Association. www.nea.org/tools/35542.htm

National Tutoring Association. 2002. Peer tutoring factsheet. Lakeland, FL: National Tutoring Association. peers.aristotlecircle.com/uploads/NTA_Peer_Tutoring_Factsheet_020107.pdf

Topping, K., and S. Ehly. 1998. Introduction to peer-assisted learning. In Peer-assisted learning, ed. K. Topping and S. Ehly, 1–23. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Yogev, A., and R. Ronen. 1982. Cross-age tutoring: Effects on tutors’ attributes. Journal of Educational Research 75 (5): 261–268.

BIODATA:

Deirdre Derrick has worked with English language students and teachers for over ten years. She was an English Language Fellow in Azerbaijan (2012–2013) and is currently working on a PhD in Applied Linguistics with a focus on language assessment.

Appendix: Online Resources for Creating a Training Packet for Tutors

Peer Tutoring … a proactive intervention for the classroom

www.cehd.umn.edu/ceed/publications/tipsheets/preschoolbehavior/peertutor.pdf

This is a brief, easy-to-read document that answers questions about how to begin and maintain a tutoring program. Although it is geared toward working with students with learning disabilities, the information applies to all types of tutoring.

Wellesley University Tutor Training Manual

This manual documents the types of logistics and content necessary to run a tutoring program (although it perhaps contains more than what an English tutoring program would need). Beginning on page 19, it discusses ways to make tutoring sessions successful, and beginning on page 55, it presents time-management skills.Tamanawis Peer Tutor Training Manual

tamanawistutors.wordpress.com/documents/peer-tutor-training-manual

This is a slightly shorter manual that contains information on effective tutoring sessions, learning styles, and good listening strategies, among other things. Again, not all the information will be relevant to an English tutoring program, but the manual itself can serve as a model.

Anoka-Ramsey Community College Tutor Training

https://www2.anokaramsey.edu/tutor_training/

This site contains ten interactive tutor-training modules, including “Introduction to Tutoring,” “Five Steps to Being Effective,” “Techniques That Work,” “Listening Skills,” and “Learning Styles.” Depending on the English level of the tutors, they could be directed to this site for specific self-study modules.

AmeriCorps’s Students Teaching Students: A Handbook for Cross-age Tutoring

This is a handbook for setting up a cross-age tutoring program. It is not intended to be given to tutors; rather, the information should be adapted for training tutors. It is particularly useful for younger tutors.

Format: Text

International Subscriptions: English Teaching Forum is distributed through U.S. Embassies. If you would like to subscribe to the print version of English Teaching Forum, please contact the Public Affairs or Cultural Affairs section of the U.S. Embassy in your country.

U.S. Subscriptions: English Teaching Forum is exempted from the Congressional restriction on distribution of Department of State-produced materials in the United States. U.S. residents who want to order the printed edition can order from the U.S. Superintendent of Documents.

The institution where we work in Buenos Aires—Asociación Ex Alumnos del Profesorado en Lenguas Vivas “Juan Ramón Fernández” (AEXALEVI)—is devoted to the teaching of foreign languages, particularly English, and it administers examinations all over Argentina. One central problem we have identified in our work in the AEXALEVI Teachers’ Centre is the compartmentalization of instruction and assessment.

For five years we held virtual and face-to-face forums with instructors from Buenos Aires and other districts, and most of these teachers reported that they generally teach the content of the syllabus as one thing, and they deal with exam training as a separate component in the course design, developed close to examination time and not before. However, when the teacher indulges in teaching to the test, the student does not have the chance to develop skills over time. For example, we have observed students who can rattle off the summary of a story, overtly learned by heart, without ever being able to answer a simple question from the examiner or interact with a peer in a communicative task. Were the students trained to recite the story? Surely they were. Were the students given opportunities to develop oral skills throughout the course so that they would be able to engage in realistic talk? We do not think so. Here lies the danger of treating course and exam, and by the same token, teaching/learning and evaluation, as two separate components rather than as an integrated whole.

At the Teachers’ Centre, we felt we needed to take a step forward to design ways to introduce changes in skill development to help students both improve their speaking ability and perform better on tests. The experience we are going to describe was born out of a concern to accomplish these goals. This article describes several techniques that allow students to structure their oral discourse in meaningful ways, which we hope will be useful for other teachers in similar contexts.

Strategies to structure oral discourse

When we teach our students how to write a composition in a foreign language, we teach them how to structure their writing. To this end, we provide pictures, guiding questions, key words, sentence starters, and model paragraphs to help them feel at ease with the difficult task ahead. However, when it comes to dealing with speaking in a foreign language—in this case, English—we may not be totally aware that oral discourse requires structuring as well. The more our students speak English in class, the more chances they have to improve their performance in English, and as a result, they are expected to perform better in oral exams. However, all learners are different, and some may need more than just opportunities for speaking in English. In our experience, some students benefit from learning strategies on how to structure oral discourse. We have observed that certain techniques help these students to gain confidence and get started in oral performance, basically because the techniques, as we will show, prevent the students from purposeless wandering when they have to give certain answers in oral interaction.

Brown (2001) highlights the importance of developing strategic competence, one of the components of the communicative competence model supporting successful oral communication (Canale and Swain 1980; Bachman 1990). Our efforts in the classroom are based on helping students think and act strategically—skills that will surely make them become more efficient communicators in English.

Thinking and routines

A large amount of research has been done in the area of learning strategies and their training; this research shows that strategy training must be explicit and contextualized in situations in which the students can appreciate the value of the strategy and that development of strategies occurs over time as they are modeled, applied, and evaluated by teachers and students (Hsiao and Oxford 2002; Cohen 2000; O’Malley and Chamot 1990; Oxford 1990; Wenden 1991).

As teachers, we had always provided our students with language banks (e.g., vocabulary relevant for the task, linkers, suitable openings and endings, useful expressions), which we worked on systematically throughout the course. However, this time we were seeking something different, something that could help students structure their oral discourse. It was then that we did research into how thinking shapes speaking by analyzing and applying the work of Ritchhart (2002) on thinking routines.

All teachers are familiar with routines, those actions that we do in class with the purpose of organizing classroom life: hands up before a speaking turn is assigned, an agenda written on the board at the beginning of each class, silent reading time on Friday afternoons. Ritchhart says that “classroom routines tend to be explicit and goal-driven in nature” and that “their adoption usually represents a deliberate choice on the part of the teacher” (2002, 86). Yet not all classroom routines are alike. Some routines help to organize students’ behavior, whereas others help to support thinking. Ritchhart calls the latter “thinking routines” and defines them as those routines that “direct and guide mental action” (2002, 89). Of the many routines that we may have in the classroom, thinking routines explicitly support mental processing by fostering it. An example is starting a fresh unit with a brainstorming task in which prior knowledge is recorded in a web. Brainstorming and webbing are thinking routines in that they “facilitate students’ making connections, generating new ideas and possibilities, and activating prior knowledge” (Ritchhart 2002, 90).

Thinking routines have certain features such as the fact that “they consist of few steps, are easy to teach and learn, are easily supported, and get used repeatedly” (Ritchhart 2002, 90). They can be singled out easily because they are named in a certain way—for example, “brainstorming, webbing, pro and con lists, Know–Want to know–Learned (KWL)” (Ritchhart 2002, 90). Apart from fostering thinking, these routines serve major purposes. Thus, a list of pros and cons may turn out to be a good way of choosing between options before we make a decision, and a KWL chart may help us record what we know about a topic, what we wish to learn about it, and finally, after the topic has been explored, what we have learned in relation to it. According to Ritchhart, “thinking routines are more instrumental than are other routines” (2002, 90). Of the examples that he provides, we selected two to begin our work, and then we developed three of our own.

An examination of two techniques

In the descriptions below we have labeled the selected routines as techniques, relying on Brown’s (2001) principles for speaking activities. Brown suggests using “techniques that cover the spectrum of learner needs from language-based focus on accuracy to message-based focus on interaction, meaning and fluency” (2001, 275). We consider that the techniques in this article fall somewhere along this continuum in that they provide support for students to engage in various classroom tasks. In addition, Brown offers useful designations that techniques must be “intrinsically motivating” and that teachers should help students “to see how the activity will benefit them” (2001, 275).

Technique 1: Say what. Say why. Say other things to try

The first technique was Say what. Say why. Say other things to try, which was suggested to Ritchhart (2002) by a colleague. It sounds straightforward and catchy, with a rhythm that Ritchhart highlights as essential for students to remember. We decided that this technique could help our students frame their answers to personal questions, a common real-life situation. In many exam situations students are generally required to answer questions of this sort as well.